November 1930

A wave of bank failures in November 1930 marks the onset of the first banking crisis of the Great Depression era. A significant increase in bank failures occurred following the collapse of a large financial conglomerate, Caldwell and Company, in Nashville, Tennessee. On November 7, the Bank of Tennessee, owned by Caldwell and Co., failed. Two other Caldwell-affiliated banks in Knoxville, Tennessee, failed five days later. The demise of Caldwell triggered runs by depositors in Tennessee, and panic spread quickly to banks in other states such as Kentucky, Arkansas, and North Carolina. The banking crisis subsided in January 1931. There were 256 bank suspensions in November and 352 in December. Overall, the banking problems during this crisis were concentrated in specific regions, and there were no widespread runs nationally.

December 11, 1930

The Bank of the United States (which despite its name was a commercial bank) in New York City fails. With deposits of about $200 million, the Bank of the United States was then the largest bank failure in U.S. history. An effort by the New York Federal Reserve Bank and the clearinghouse banks in New York City to save the bank by merging it with other city banks was unsuccessful. Some scholars attribute its failure to the banking panic that occurred in late 1930, while others believe it was insolvent at the time of its failure.

December 11, 1930

December 31, 1930

During 1930, there are about 1,350 bank suspensions. The number of commercial banks operating in the United States has declined to 23,769.

April 1931

The first Great Depression-era banking crisis had subsided in January 1931, and the economy had shown signs of improvement in the early months of 1931. However, beginning in April 1931, bank suspensions, deposit losses, and currency holding increased significantly. This second banking crisis would last until August 1931. During this period, 563 banks suspended. These suspensions were largely concentrated in the Federal Reserve Districts of Chicago, Minneapolis, Cleveland, and Kansas City. As with the first banking crisis, the second banking crisis was also regional.

September 1931

The third major Depression-era banking crisis began with the departure of Britain from the gold standard on September 21, 1931, and lasted until the end of the year. The number of bank failures, deposits of failed banks, and currency held by the public increased sharply from September to October. Unlike the two previous crises in 1930 and earlier in 1931, which were regional, the crisis in the fall of 1931 turned into a nationwide banking crisis. The banking system faced both an external drain of gold and an internal currency drain in September and October. The external drain of gold followed immediately after Britain departed from the gold standard. Uncertainty about the gold convertibility of the dollar led to a reduction of the U.S. gold stock. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York responded to the outflow of gold by increasing the discount rate on October 9. While the external drain subsided in October, the discount rate increase might have adversely affected the domestic economy. Between September and October, there were 817 bank suspensions. The number of bank suspensions and the amount of deposits in failed banks decreased significantly in November. There was also a notable decrease in currency hoarded by the public. By December 1931, the crisis had subsided.

October 13, 1931

The Hoover Administration announces the formation of the National Credit Corporation (NCC), which was intended to lend funds to illiquid banks. The NCC was a private-sector organization made up of banks. Although it made loans and some have argued that it had at least some brief positive psychological stabilizing effects, the NCC overall proved ineffective and was soon replaced by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation.

December 31, 1931

During 1931, there are about 2,300 bank suspensions.

January 22, 1932

The Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) Act of 1932 is signed into law by President Herbert Hoover. The RFC, modelled on the War Finance Corporation created in 1918, would facilitate economic recovery by lending to financial institutions; the intention was that these loans would bolster banker confidence and so increase commercial credit. The RFC's initial capital came from the sale of $500 million in stock to the U.S. Treasury and an additional $1.5 billion from bonds that the Treasury sold to the public. Although originally conceived of as an emergency agency during the Great Depression, the RFC had a renewed mission during World War II: aiding the war effort through the creation of several subsidiary corporations. The RFC's lending authority ended in 1953, but it did not formally shut down until 1957.

https://eh.net/encyclopedia/reconstruction-finance-corporation/

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/rcf/rfc_19320122_act.pdf

See Michael Gou et al., “Banking Acts of 1932,” Federal Reserve History, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/banking-acts-of-1932

James S. Olson, “Saving Capitalism: The Reconstruction Finance Corporation and the New Deal, 1933-1940,” (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988).

February 27, 1932

The Banking Act of 1932 is signed into law by President Herbert Hoover. The law contained two main elements: the first permitted Federal Reserve Banks to lend to Federal Reserve member banks on a wider range of assets but at a higher interest rate; the second authorized the Federal Reserve banks to use government securities as collateral for Federal Reserve notes to increase the supply of money in circulation. By June, adopting an expansionary policy, the Federal Reserve System had purchased more than $1 billion in government securities, temporarily reversing the deflationary problems that beset the country. However, the Federal Reserve ended these policies in the summer of 1932. When first passed, this law was known as the Glass-Steagall Act, but that name has historically been attached to the provisions of the Banking Act of 1933 that separated commercial banking and investment banking.

See Michael Gou et al.,“Banking Acts of 1932,” Federal Reserve History, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/banking-acts-of-1932 .

July 22, 1932

In response to the severe liquidity problems mortgage lenders faced during the Great Depression, President Herbert Hoover signs the Federal Home Loan Act into law. The act establishes the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) System, which consists of 12 federally chartered regional banks owned by its member financial institutions. Any building and loan association, saving and loan association, insurance company, or savings bank chartered and regulated by the state and federal government could become a member. Each bank's capital was provided by member institutions and the federal government. Member institutions would receive dividends from the stock they owned in the bank and had the right to vote for the bank's board of directors. The law also creates the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, which supervises the FHLBs. Member institutions in each district have access to liquidity in the form of advances, which are cash loans, subject to collateral requirements, with eligible collateral consisting primarily of mortgages. The regional banks fund their lending to member institutions by issuing bonds.

https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/statement-about-signing-the-federal-home-loan-bank-act

Congressional Research Service. “The Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) System and Selected Policy Issues.” August 27, 2020, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46499/2 .

October 31, 1932

Nevada is the first state to declare a banking holiday when runs on individual banks threaten the state's banking system. Although the Nevada holiday was local, it attracted national attention and may have influenced officials in Iowa and Louisiana to declare statewide holidays in January and February of 1933, a trend which continued with Michigan's declaration of a bank holiday in February. These statewide holidays created added uncertainty for depositors. Also, the uncoordinated state holidays contributed to the banking panic in 1933, because a bank holiday in one state could increase pressure on banks in other states as banks in states with holidays could withdraw funds from correspondent banks in other states to improve their own condition. Also, depositors in other states might become worried that a holiday could be declared and withdraw their deposits fearing their funds could become unavailable.

December 31, 1932

During 1932, there are about 1,450 bank suspensions.

January 1933

In March 1932, the Senate had authorized an investigation into manipulative practices in the securities industry. It had made little headway until now, with the appointment of a new chief counsel, Ferdinand Pecora. The committee also expanded the range of its investigation to include banking practices. The committee's hearings, which continued into 1934, at times became riveting public spectacles, drawing attention to malfeasance by both securities dealers and bankers. Pecora's investigation of National City Bank and its securities affiliate, the National City Company, received considerable attention. The Pecora hearings helped to bring about the passage of the Glass-Steagall provisions of the Banking Act of 1933, which separated banking and securities finance, and the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission. The committee issued its final report in 1934.

https://www.senate.gov/about/powers-procedures/investigations/pecora.htm

February 14, 1933

Michigan declares a statewide banking holiday, sparking state holidays in many other states and a deterioration of depositor confidence throughout the country. Banking problems had begun in Detroit. Banks affiliated with the two major local banking groups, the Detroit Bankers Company and the Union Guardian Group, sustained heavy deposit withdrawals. The troubled banks had made substantial real estate loans and suffered losses. One of the distressed banks, the Union Guardian Trust, part of the Union Guardian Group, requested a large loan from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). The negotiations broke down between the Guardian Group; Henry Ford, who had a substantial personal investment in the Detroit banks; and the RFC. Officials insisted Ford subordinate his $7 million deposits as a condition for granting the RFC loan. Ford refused to provide further commitment to recapitalize the troubled banks and threatened to withdraw his deposits from the banking system. The Detroit banks had extensive networks of affiliated banks, and their failures had severe repercussions for the rest of the banks in Michigan. The Governor was forced to declare a banking holiday after the negotiations collapsed.

February 1933

The fourth major banking crisis of the Great Depression era occurs. The February 14 Michigan bank holiday had immediate repercussions on banking in the surrounding states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, and the erosion of depositor confidence eventually spread to other parts of the country. Currency hoarding greatly increased by late February, and banks in New York City faced increasing withdrawal pressures as demand for currency increased. Between February 14 and March 3, many states declared bank holidays or imposed restrictions on deposit withdrawals. Banks in New York City faced increased withdrawals as demand for currency increased. By the beginning of March, there had been 400 bank suspensions, and another 3,400 bank suspensions would occur by March 16. Several factors contributed to the nationwide loss of depositor confidence, including uncertainty about the policies of the incoming Roosevelt administration. The congressional requirement that the names of Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) borrowers be public might have reduced banks' willingness to borrow from the RFC and so decreased the RFC's effectiveness. In addition, the Federal Reserve responded to an external gold drain by raising the discount rate, but it did not conduct major open market purchases.

Kristie M. Engemann, “ Banking Panics of 1931-33,” Federal Reserve History.

March 6, 1933

President Franklin D. Roosevelt declares a nationwide bank holiday. By the time of his inauguration on March 4, the banking system was in complete disarray. Depositors were hoarding cash and 48 states had either declared a statewide bank holiday or restricted deposit withdrawals. However, uncoordinated responses by individual states were not an effective solution to a nationwide panic and hoarding of cash. On March 6, President Roosevelt issued a proclamation ordering the immediate suspension of all banking transactions, shutting down the entire banking system until March 9. On March 9, Congress enacted the Emergency Banking Act and the banking holiday was extended. The banking holiday lasted until March 13–15, depending on the bank’s location. Depositors had limited or no access to banking services. Federal government officials were therefore faced with the task of reopening banks. Banks could reopen only if federal or state banking authorities deemed them capable of resuming business. Banks began to reopen on March 13. By March 15, half of the country’s banks with a majority of the nation’s banking resources resumed business. More than 5,000 banks reopened later or were closed. With the orderly reopening of the banks, the banking crisis subsided and deposits flowed back into the banking system.

https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/epr/09v15n1/0907silb.pdf

March 9, 1933

The Emergency Banking Act of 1933 is signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The law retroactively legalizes the national bank holiday and sets standards for the reopening of banks. The law also expands the Reconstruction Finance Corporation's (RFC's) authorities in order to address the banking crisis: rather than just lending to banks, the RFC can now strengthen them by purchasing preferred stock and capital notes of banks. To ensure an adequate supply of currency, the law also provides for the issuance of Federal Reserve Notes, which were to be backed by U.S. government securities. The bill passes hurriedly during a chaotic period. Few members of Congress know the contents of the bill; reportedly in the House, Rep. Henry Steagall had the only copy. Waving it over his head, Steagall shouted, “Here's the bill. Let's pass it.” No amendments are permitted and after only 40 minutes of debate, it passes. The Senate also passes the bill without amendment.

https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/emergency-banking-act-of-1933

March 12, 1933

President Franklin D. Roosevelt gives his first Fireside Chat on the radio. The subject is banking.

June 16, 1933

The Banking Act of 1933 is signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

This law creates the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), by far the most controversial element of the statute. The law puts in place a Temporary Fund that would be effective January 1, 1934, with a basic coverage level of $2,500. The U.S. Treasury and the 12 Federal Reserve Banks supply the FDIC's initial capital of approximately $289 million. FDIC member banks will be assessed 0.5 percent of insured deposits, with half to be collected immediately and the other half on call.

Banks that were members of the Federal Reserve (e.g., national banks and state member banks) automatically will become FDIC members. Solvent nonmember state-chartered banks, upon application and examination, will also qualify for membership in the Temporary Fund. The law also mandates that nonmember banks that want to retain deposit insurance coverage must apply to become Federal Reserve member banks by July 1, 1936 (a deadline that was later extended, and the requirement was later removed altogether).

In addition, the FDIC will become the federal supervisor for state nonmember banks (before this law, such banks had been subject only to state supervision). With regard to failed bank resolution, the FDIC is required to be the receiver when a national bank fails; the FDIC could serve as receiver when state-chartered banks fail, but it took a number of years before the FDIC routinely served as receiver in such cases. The law provides for a Permanent Fund to be implemented in six months, with a different insurance scheme. But this would-be permanent plan never comes into effect because the Temporary Fund is extended and a new set of permanent deposit insurance provisions are enacted under the Banking Act of 1935.

The law also includes provisions that prohibit banks from engaging in the securities business, a prohibition that would not be removed until 1999. It also caps interest rates that banks could pay, so-called Regulation Q, limits, that would remain in place until the 1980s.

https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/glass-steagall-act

September 11, 1933

Walter J. Cummings (1879-1967), becomes the first Chairman of the FDIC and serves until February 1, 1934. A native of Illinois, Cummings entered banking as a clerk at age 18 but became a partner in a railroad equipment company and later organized the Cummings Car and Coach Company. He was named executive assistant to the Secretary of the Treasury in March 1933. Having overseen the successful establishment of the Corporation, Cummings left the FDIC to head the Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Company.

September 11, 1933

October 1, 1933

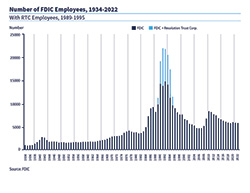

The FDIC's Division of Examination is created. Its first responsibility is to examine state nonmember banks for admission to the Temporary Fund. Examiners from the OCC and state banking supervisors were transferred or seconded to the FDIC, and 47 field offices are established around the country. At its peak, this temporary examination force had nearly 1,700 examiners and 900 support staff. Many examiners were on loan from the OCC or state bank authorities. The examiners undertake the difficult job of examining by year-end the thousands of state nonmember banks that have applied to become FDIC members.

December 31, 1933

During 1933, there are about 4,000 bank suspensions, with 3,800 by March 16. The number of commercial banks operating in the United States has dropped to just over 14,000, about half as many as in 1920.

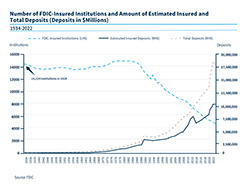

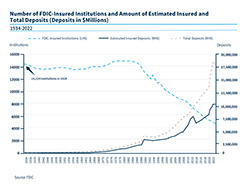

January 1, 1934

FDIC insurance goes into effect. A total of 12,551 commercial banks with total insured deposits of about $11 billion gain FDIC insurance on its first day.

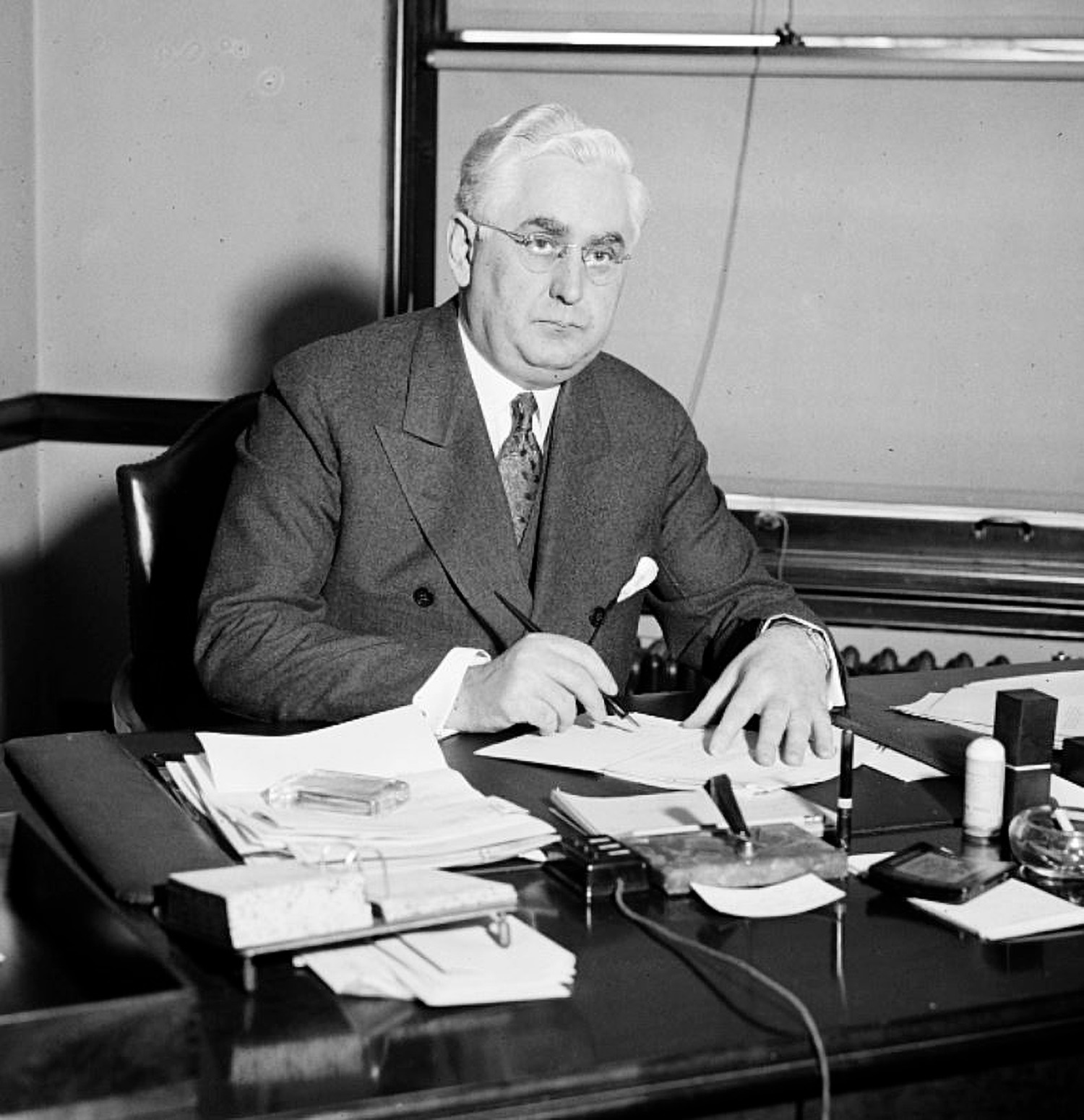

February 1, 1934

Leo T. Crowley (1889-1972) becomes the second Chairman of the FDIC and serves until January 5, 1946, by far the longest-serving FDIC Chairman. Before coming to Washington in 1934, Crowley, a native of Wisconsin, had been president of the Bank of Wisconsin. Earlier in his life, he was head of the General Paper and Supply Company, and he purchased several banks before the Great Depression. When the Depression hit, Crowley organized the Wisconsin Banking and Review Board. When he was FDIC Chairman, beginning in 1943, Crowley also served as Alien Property Custodian, Chief of the Office of Economic Warfare, and head of the Foreign Administration. After he resigned from all of his government posts, he became Chairman of the Board of the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pacific Railroad.

June 16, 1934

Legislation is enacted that extends the Temporary Fund to July 1, 1935. The law allows insured nonmember banks to terminate their membership in the Temporary Fund on July 1 (only 21 did so). The law also increases the basic deposit insurance coverage level to $5,000 (an increase supported by the FDIC), defers the requirement that insured nonmember banks become Federal Reserve members for an additional year, and makes banks in Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Alaska, and the Virgin Islands eligible for deposit insurance. The law also requires each insured bank to display signs indicating their insured status.

June 27, 1934

The National Housing Act of 1934 becomes law. The law’s importance in the history of deposit insurance is its creation of the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC) to provide deposit insurance coverage to savings institutions. FSLIC coverage mirrors FDIC coverage until the FSLIC is abolished in 1989. The law also creates the Federal Housing Administration and helps stabilize the housing market.

July 3, 1934

The FDIC makes its first payments to insured depositors of the Fon Du Lac State Bank in East Peoria, Illinois, which had failed on May 28, 1934.

The FDIC makes its first payment to insured depositors of the Fon Du Lac State Bank in East Peoria, Illinois

December 31, 1934

The FDIC ends its first year with 846 employees and total fund assets of about $334 million, having handled nine insured bank failures during the year. By year-end, 14,146 commercial banks are insured, with about $17 billion in insured deposits (much of the increase in insured deposits was due to the increase in the coverage limit from $2,500 to $5,000 in June). More than 1,000 (1,068) state-chartered commercial banks, with a total of about $500 million in deposits, remain uninsured at year-end.

June 28, 1935

The U.S. Congress passes a joint resolution extending the life of the Temporary Fund for 60 days to allow time for the Banking Act of 1935 to pass.

August 23, 1935

The Banking Act of 1935 is signed into law by FDR making the FDIC permanent. The deposit insurance provisions include:

- Maintaining the $5,000 coverage limit. This would mean that approximately 98 percent of depositors in U.S. banks would be fully covered.

- Changing the assessment system to one with a flat rate of 8.33 basis points, levied on total deposits. The FDIC had calculated this would likely suffice to handle failed bank losses in the future. The change from insured to total deposits would be both easier to calculate and would reduce the proportionate burden on small banks in supporting the fund.

- Removing the provisions whereby banks purchased stock in the FDIC.

- Changing the requirement that nonmember banks become Federal Reserve members to retain deposit insurance, now limiting the requirement to banks with more than $1 million in deposits and pushing the compliance date to 1942 (the requirement that any nonmember bank convert to Federal Reserve membership was quietly removed altogether in 1939).

- Expanding the criteria the FDIC uses to approve deposit insurance applications from nonmember banks to better address risk to the fund.

- Permitting the FDIC to terminate a nonmember bank’s deposit insurance if the institution was found to be operating in an unsafe or unsound manner and did not correct the problems.

- Giving the FDIC the authority to purchase bank assets to facilitate mergers and reduce costs to the fund.

- Allowing the FDIC to pay depositors directly, rather than through the mechanism of a newly chartered national bank (a Deposit Insurance National Bank or DINB).

https://www.fdic.gov/about/financial-reports/reports/archives/fdic-ar-1935.pdf

The deposit insurance provisions of the 1935 Act were largely uncontroversial. The provisions concerning the Federal Reserve were much more contentious. For a discussion of those changes, see Michael Gou et al., “Banking Acts of 1932,” Federal Reserve History, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/banking-act-of-1935 .

June 20, 1939

Public Law 76-135 repeals the provision that requires state nonmember banks with more than $1 million in deposits to become members of the Federal Reserve System in order to maintain their FDIC-insured status, permanently frustrating Sen. Carter Glass's hope that his reluctant support for deposit insurance in 1933 would eventually lead to a unified banking system with all commercial banks as Federal Reserve members.