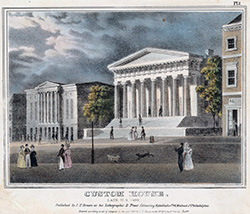

The Second Bank of the United States is chartered.

The country found itself without a national bank after the First Bank of the United States closed its doors in 1811 following the decision by Congress not to renew the bank's charter. The consequences of the War of 1812, however, galvanized support for a new national bank as a solution to the country's economic and financial problems. U.S. exports had collapsed, and federal government revenues from customs duties declined significantly due to wartime disruption of foreign trade. As a result, the U.S. economy suffered significant dislocation and was burdened with heavy debt. Despite strong opposition, on April 10, 1816, President James Madison signed into law a bill creating the Second Bank of the United States. The Second Bank began operations at its main branch in Philadelphia in January 1817 with a 20-year charter. It provided fiscal services to the federal government and also functioned as a commercial bank. In 1828, Andrew Jackson was elected President. Jackson, who had a strong distrust of banks and viewed both the first and second Banks as unconstitutional and a threat to states' rights, in July 1832 vetoed a bill to renew the Second Bank's charter. Having won re-election in 1832 with the bank as the crucial issue, President Jackson in 1833 ordered federal government deposits removed from Second Bank and redeposited in state banks. Strong anti-bank sentiment and lack of sufficient political support eventually sealed Second Bank's fate. Its charter was not renewed and the bank became a private Pennsylvania corporation in 1836.

Panic of 1819

The panic of 1819 had its roots in domestic and international factors brought about by the War of 1812 and the Napoleonic Wars in Europe. These conflicts contributed to the expansion of the U.S. economy, which was marked by thriving commerce and agriculture due to increased wartime production capacities and strong international demand for American commodities such as cotton and wheat. The fast-growing economy coupled with the country's westward expansion led to a boom in real estate in the West and spurred investment there. Banks, particularly those in the West, financed many of these real estate purchases and projects. With little effective supervision, many newly chartered banks issued notes beyond their capacity to redeem them in specie (money in coin rather than notes). Unfettered note issuance and lending contributed to rapid growth in the credit supply, and monetary conditions became chaotic. The creation of the Second Bank in 1816 was intended to restore the convertibility of state bank notes into specie and rein in the oversupply of money. However, not only did the policies pursued by the Second Bank during its early years fail to achieve these objectives, the bank's policies actually worsened the monetary situation by extending more loans via its branches. Eventually, the overextended Second Bank tightened credit and reduced loan supply beginning in 1818. The dramatic change in money and credit supply induced by Second Bank's tightening policy led to many bank failures and loan defaults, and the overall reduction in economic activity caused severe deflation and recession.

James Narron, David R. Skeie, and Donald P. Morgan, "Crisis Chronicles: The Panic of 1819—America's First Great Economic Crisis,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Liberty Street Economics, December 5, 2014.

Clyde A. Haulman, “The Panic of 1819: America's First Great Depression,” Museum of American Finance, Financial History (Winter 2010): 20-24.

April 2, 1829

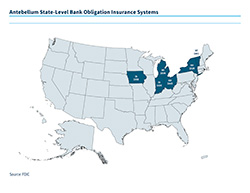

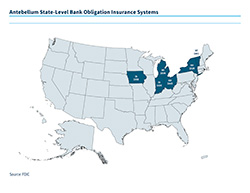

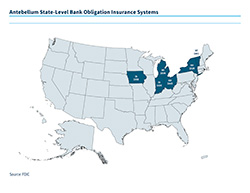

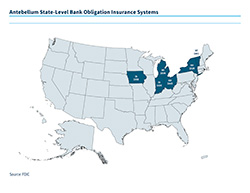

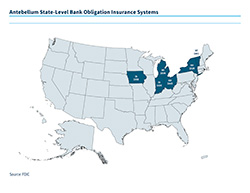

New York passes a law insuring bank obligations. New York was the first state to use the insurance principle to protect bank creditors, adopting a program on April 2, 1829, and making it fully operational in 1831. The plan created an insurance fund paid for by participating banks. The insurance fund served as a guaranty for the debts of failed participating banks. Under the original plan, debts included deposits and circulating notes. However, in 1842, as debts of failed banks exceeded the amount available from the fund, the law was amended so that insurance would apply only to circulating notes. The original intention of the plan was to include all banks in the insurance system, but the inclusion of all banks was abandoned in 1838 with New York's adoption of free banking and not requiring free banks to participate in the insurance system. The system came under financial pressure with several failures in the early 1840s, but a law addressed these financial difficulties by authorizing the issuance of bonds that could be sold to obtain funds or paid directly to bank creditors. The insurance system also required participating banks to be examined regularly, in what appears to be the first time such scheduled bank examination was applied by law to an entire banking system. The New York system become inoperative in 1866 when the charters of the last of the participating banks expired. Ninety-eight percent of insured obligations in failed banks were paid to bank creditors, either as insurance payments or receiver dividends.

For a brief discussion of the six bank obligation insurance systems put in place before the Civil War, see FDIC Annual Report, 1953, 47ff, https://www.fdic.gov/about/financial-reports/reports/archives/fdic-ar-1953.pdf .

January 1831

The Oxford Provident Building Association, the first building and loan, is organized in Frankford, Pennsylvania.

November 9, 1831

Vermont passes a law insuring bank obligations. As in New York, an insurance fund was created to pay creditors of failed banks, and insurance covered both deposits and circulating notes. Under the original plan, all banks chartered or re-chartered after 1831 were subject to the insurance law unless specifically exempted. In 1840, new legislation provided that all banks subsequently chartered or re-chartered would have the option to enter or remain outside of the insurance system. Free banks, which were first established in 1851, were not included in the system. Only two insured banks failed while the system, which lasted until 1866, was in operation. Seventy-two percent of claims against the insurance fund were paid, often long after the banks had failed, but more than 40 percent of the obligations were never presented for payment.

For a brief discussion of the six bank obligation insurance systems put in place before the Civil War, see FDIC Annual Report, 1953, 47ff, https://www.fdic.gov/about/financial-reports/reports/archives/fdic-ar-1953.pdf .

January 28, 1834

Indiana establishes a mutual guaranty system to protect bank obligations. Unlike the systems in New York and Vermont, the Indiana insurance system did not have an insurance fund. Instead, all participating banks were required to mutually guarantee each other's debts. The banking system in Indiana was unusual in that, until free banking was adopted in 1851, it consisted of a “state” bank made up of a federation of independent banks, and membership in the insurance system was restricted to those banks. The state bank's charter expired in 1857, and the bank was replaced by another slightly different “state” bank. Indiana's insurance system ended in 1865 when most of the participating banks converted to national bank charters. None of the insured banks failed while the system was in operation.

For a brief discussion of the six bank obligation insurance systems put in place before the Civil War, see FDIC Annual Report, 1953, 47ff, https://www.fdic.gov/about/financial-reports/reports/archives/fdic-ar-1953.pdf .

March 28, 1836

Michigan passes a law providing for the protection of bank creditors.

The Michigan system established an insurance fund paid for by participating banks, which could not withdraw from the insurance system. Insurance covered circulating notes, deposits, and other bank liabilities. In 1837, Michigan adopted a free banking statute, but unlike other states, included free banks in the insurance system. Thirty free banks were opened in 1837, coinciding with the panic that year. At the end of 1837, the insurance fund had just $145.14 available. By 1839 (possibly earlier), the fund was insolvent, and it is likely that the fund never paid any money to creditors of failed banks. The fund officially ended in 1842, by which time essentially the entire Michigan banking system had collapsed.

For a brief discussion of the six bank obligation insurance systems put in place before the Civil War, see FDIC Annual Report, 1953, 47ff, https://www.fdic.gov/about/financial-reports/reports/archives/fdic-ar-1953.pdf .

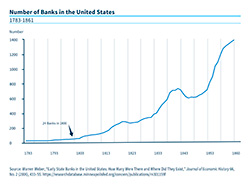

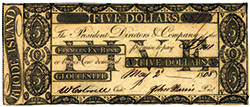

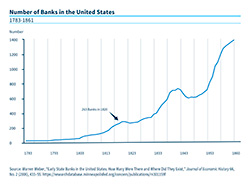

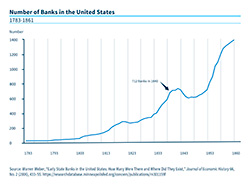

The Free Banking Era begins in 1837. Apart from the First and Second Banks of the United States, bank regulation since the country's founding had been left to the states and banks were chartered by state legislatures. Beginning in 1837 with Michigan, however, many states adopted so-called free banking laws. Eventually 18 states adopted such laws, which had few entry requirements. Free banks operated alongside chartered banks but were more likely to be in less-populated rural areas. Free banking allowed anyone with a certain minimum amount of capital to start a bank, which could issue bank notes provided that the bank deposited government bonds (typically those issued by the state) with the state banking authority as collateral. In return, the bank would usually be permitted to issue bank notes of a value equal to the deposited bonds. One consequence of this system was that a bond price decline would depreciate the values of bank assets and lead to bank runs and failures. Bank notes were a promise by the issuing bank to pay a specified amount of specie on demand. Thousands of different types of bank notes circulated during this period and were exchanged at various discount rates according to the perceived soundness of their issuers and the distance from the issuing bank. Free banking laws protected noteholders. When a bank failed to redeem its notes, the state banking authority would close the bank and sell its deposited collateral to repay all noteholders. The stability of the free banking system varied in different states. New York was considered a well-functioning free banking system, while Midwest free banking states experienced severe banking unrest. The free banking era ended with the passage of the National Bank Acts during the Civil War.

Panic of 1837

In the years leading up to the panic, the United States experienced economic and financial expansion. The rapid growth in money and credit supply to the economy by the banking system fueled the purchases of public land in the western frontier and led to an increase in land and commodity prices. Domestic policies and international forces contributed to the boom and the overexpansion in bank credit leading up to the Panic of 1837. Domestically, President Jackson's banking policies led to the demise of the Second Bank. Without a national bank to impose discipline on the banking practices of state-chartered banks, credit supply grew rapidly and lending standards were lax. International factors also contributed to the credit boom as large amounts of specie (gold and silver) flowed into the United States from abroad as international investors hoped to profit from the fast-growing U.S. economy. The changing domestic banking landscape and the influx of foreign capital sowed the seeds for the bust as many banks over-issued banknotes and gave out too many loans. The banking policies implemented by Jackson's administration and the reverse of international specie flows set the stage for the Panic of 1837. Jackson's policies aimed to aggressively limit the issuance and use of paper currency in the economy. In 1836, Jackson signed the Specie Circular executive order. While the intent was to curb land speculation, the Specie Circular mandated that government land could be purchased only with specie, causing a drain of specie from banks in the money centers, particularly banks in New York. The Specie Circular heightened demand for specie and disrupted the flow of funds in the banking system. The banking system also faced increasing liquidity pressure internationally as the Bank of England raised its discount rate due to concerns about a loss of specie. Increasing demand for specie and withdrawal pressures led banks in New York City to eventually suspend the convertibility of their notes for specie, which caused a general panic around the country. The panic led to a collapse of credit supply in the banking system and a severe decline in economic activities.

February 24, 1845

Ohio becomes the fifth state to pass a law for the protection of bank creditors. This law created a state system of branch banks that were independently owned (similar to Indiana's) and permitted a limited number of banks to be created outside that system (which was expanded with a free banking law in 1851). Membership in the insurance system was limited to the branch banks, and only circulating notes were protected. Participating banks collectively guaranteed the circulating notes of the banks under the system by paying into a “safety fund,” which would be used to reimburse losses to member banks if one of the system's banks became insolvent and could not redeem its notes. Several member banks became insolvent or faced financial difficulties while the system was in operation, but no noteholder of a failed participating bank suffered a loss, so the insurance system was by that measure successful. Since the legal authorization for the branch banks was to expire in 1866, many Ohio banks converted to national banks. By the end of 1865, Ohio banking consisted of either free or national banks, and the insurance system became inoperative.

For a brief discussion of the six bank obligation insurance systems put in place before the Civil War, see FDIC Annual Report, 1953, 47ff, https://www.fdic.gov/about/financial-reports/reports/archives/fdic-ar-1953.pdf .