Recent Bank Failures and the Federal Regulatory Response

Chairman Brown, Ranking Member Scott and Members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to appear before the Committee today to address recent bank failures and the Federal regulatory response.

On March 10, 2023, just over two weeks ago, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Santa Clara, California, with $209 billion in assets at year-end 2022, was closed by the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation (CADFPI), which appointed the FDIC as receiver. The failure of SVB, following the March 8, 2023 announcement by Silvergate Bank that it would wind down operations and voluntarily liquidate,1 signaled the possibility of a contagion effect on other banks. On Sunday, March 12, 2023, just two days after the failure of SVB, another institution, Signature Bank, New York, New York, with $110 billion in assets at year-end 2022, was closed by the New York State Department of Financial Services (NYSDFS), which also appointed the FDIC as receiver. With other institutions experiencing stress, serious concerns arose about a broader economic spillover from these failures.

After careful analysis and deliberation, the Boards of the FDIC and the Federal Reserve voted unanimously to recommend, and the Treasury Secretary, in consultation with the President, determined that the FDIC could use emergency systemic risk authorities under the Federal Deposit Insurance Act (FDI Act)2 to fully protect all depositors in winding down SVB and Signature Bank.3

It is worth noting that these two institutions were allowed to fail. Shareholders lost their investment. Unsecured creditors took losses. The boards and the most senior executives were removed. The FDIC has authority to investigate and hold accountable the directors, officers, professional service providers and other institution-affiliated parties of the banks for the losses they caused to the banks and for their misconduct in the management of the banks.4 The FDIC has already commenced these investigations.

Further, any losses to the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) as a result of uninsured deposit insurance coverage will be repaid by a special assessment on banks as required by law. The law provides the FDIC authority, in implementing the assessment, to consider “the types of entities that benefit from any action taken or assistance provided.”5

The FDIC has now completed the sale of both bridge banks to acquiring institutions. New York Community Bancorp’s Flagstar Bank is the acquiring institution for Signature Bridge Bank, N.A., and First-Citizens Bank & Trust Company is the acquiring institution for Silicon Valley Bridge Bank, N.A.6

My testimony today will describe the events leading up to the failure of SVB and Signature Bank and the facts and circumstances that prompted the decision to utilize the authority in the FDI Act to protect all depositors in those banks following these failures. I will also discuss the FDIC’s assessment of the current state of the U.S. financial system, which remains sound despite recent events. In addition, I will share some preliminary lessons learned as we look back on the immediate aftermath of this episode.

In that regard, the FDIC will undertake a comprehensive review of the deposit insurance system and will release a report by May 1, 2023, that will include policy options for consideration related to deposit insurance coverage levels, excess deposit insurance, and the implications for risk-based pricing and deposit insurance fund adequacy. In addition, the FDIC’s Chief Risk Officer will undertake a review of the FDIC’s supervision of Signature Bank and will also release a report by May 1, 2023. Further, the FDIC will issue in May 2023 a proposed rulemaking for the special assessment for public comment.

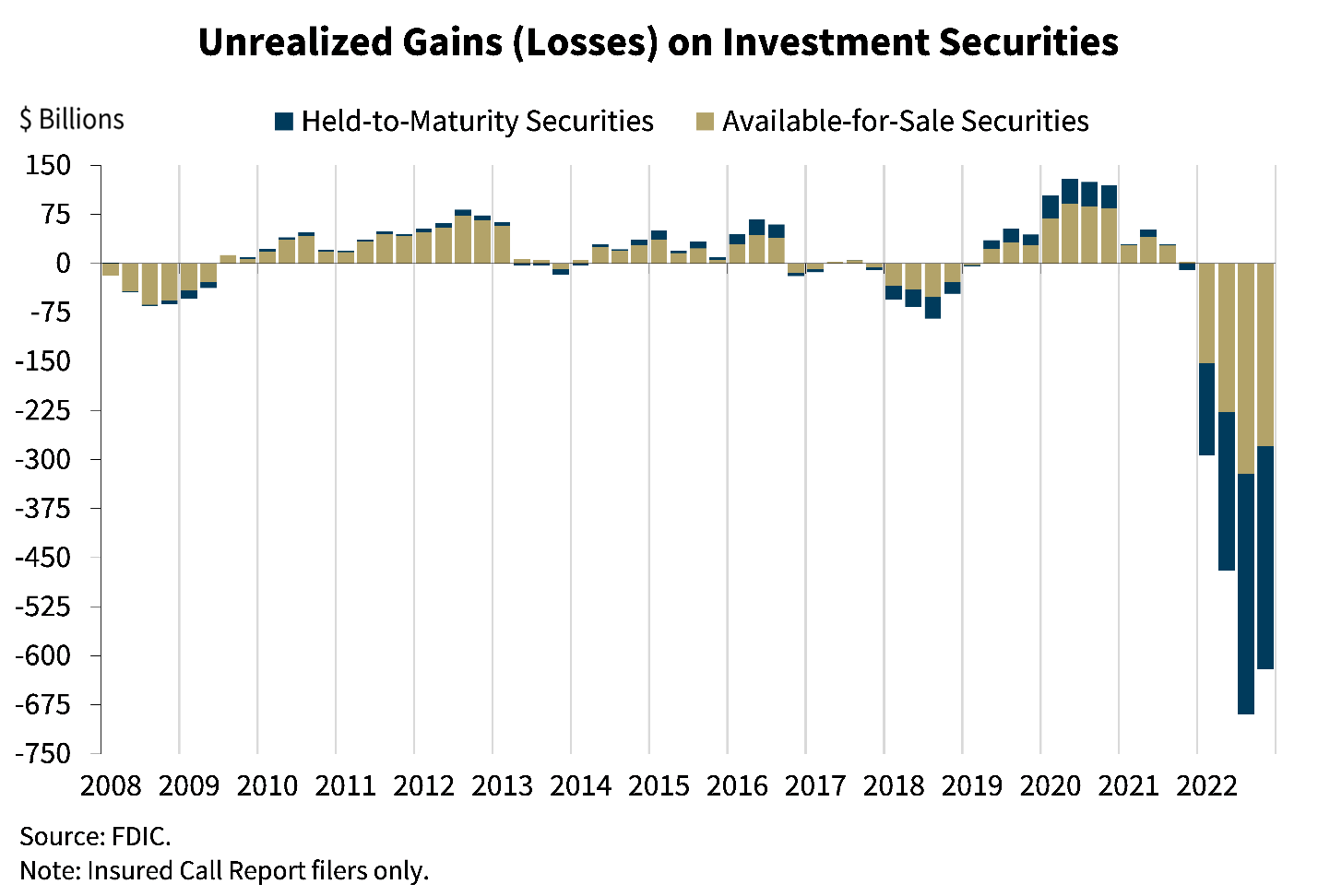

The two bank failures also demonstrate the implications that banks with assets over $100 billion can have for financial stability. The prudential regulation of these institutions merits serious attention, particularly for capital, liquidity, and interest rate risk. This would include the capital treatment associated with unrealized losses in banks’ securities portfolios. Resolution plan requirements for these institutions also merit review, including a long-term debt requirement to facilitate orderly resolution.

Economic Conditions

On February 28, 2023, the FDIC released the results of the Quarterly Banking Profile, which provided a comprehensive summary of financial results for all FDIC-insured institutions for the fourth quarter of last year. Overall, key banking industry metrics remained favorable in the quarter.7 Loan growth continued, net interest income grew, and asset quality measures remained favorable. Further, the industry remained well-capitalized and highly liquid, but the report also highlighted a key weakness in elevated levels of unrealized losses on investment securities due to rapid increases in market interest rates. Unrealized losses on available–for–sale and held-to-maturity securities totaled $620 billion in the fourth quarter, down $69.5 billion from the prior quarter, due in part to lower mortgage rates. The combination of a high level of longer-term asset maturities and a moderate decline in total deposits underscored the risk that these unrealized losses could become actual losses should banks need to sell securities to meet liquidity needs.

This latent vulnerability within the banking system would combine with several other prevailing conditions to form a key catalyst for the subsequent failure of SVB and systemic stress experienced by the broader banking system.

The Wind Down of Silvergate Bank

Silvergate Bank, La Jolla, California, with $11.3 billion in assets as of December 31, 2022, had a business model focused almost exclusively on providing services to digital asset firms. Following the collapse of digital asset exchange FTX in November 2022, Silvergate Bank released a statement indicating that it had $11.9 billion in digital asset-related deposits, and that FTX represented less than 10 percent of total deposits in an effort to explain that its exposure to the digital asset exchange was limited.8 Nevertheless, in the fourth quarter of 2022, Silvergate Bank experienced an outflow of deposits from digital asset customers that, combined with the FTX deposits, resulted in a 68 percent loss in deposits – from $11.9 billion in deposits to $3.8 billion.9 That rapid loss of deposits caused Silvergate Bank to sell debt securities to cover deposit withdrawals, resulting in a net earnings loss of $1 billion.10 On March 1, 2023, Silvergate Bank announced it would be delaying issuance of its 2022 financial statements and indicated that recent events raised concerns about its ability to operate as a going concern, which resulted in a steep drop in Silvergate Bank’s stock price.11 On March 8, 2023, Silvergate Bank announced that it would self-liquidate.12

The troubles experienced by Silvergate Bank demonstrated how traditional banking risks, such as a lack of diversification, aggressive growth, maturity mismatches in a rising interest rate environment, and sensitivity to liquidity risk, when not managed adequately, could combine to lead to a bad outcome. Many of these same risks were also present in the failure of SVB.

The Failure of Silicon Valley Bank

SVB was established in San Jose, California, on October 17, 1983. SVB’s approximately $191.4 billion in deposit liabilities as of December 31, 2022, were associated with its commercial and private banking clients, mostly linked to businesses financed through venture capital. The bank did not maintain a large retail deposit business. Total assets grew rapidly from under $60 billion at the end of 2019 to $209 billion by the end of 2022,13 coinciding with rapid growth in the innovation economy and a significant increase in the valuation placed on public and private companies. This influx of deposits was largely invested in medium- and long-term Treasury and Agency securities. SVB also had significant cross-border operations, with a subsidiary in the United Kingdom and branches in Germany, Canada, and the Cayman Islands.

On the same day that Silvergate Bank announced its self-liquidation, SVB announced that it had sold substantially all of its available-for-sale securities portfolio at a $1.8 billion after tax loss.14 SVB simultaneously announced an attempt to raise approximately $2.25 billion through the issuance of common equity and mandatory convertible preferred shares via an underwritten public offering and planned private investment.15 The following day, SVB’s share price dropped 60 percent. In an attempt to quell the rising concerns of the bank’s depositors and borrowers, the Chief Executive Officer of SVB urged venture capital clients to remain calm and keep their deposits in the institution. The appeal did not have the intended effect.16 Many of SVB’s venture capital customers took to social media to urge companies to move their deposit accounts out of SVB.17 By the end of the day on Thursday, March 9, 2023, $42 billion in deposits had left the bank.

The evening of March 9, the FDIC was informed by SVB’s primary federal regulator, the Federal Reserve, of the deposit run, subsequent funding shortfalls and that the bank was unlikely to have adequate liquidity to meet the demands of depositors and other creditors. FDIC staff engaged with the chartering authority, the CADFPI, shortly thereafter. FDIC staff worked through the night with SVB’s primary regulators in an effort to put a resolution strategy in place. At 11:15 a.m., EST, on March 10, 2023, SVB was closed by the CADFPI, which simultaneously appointed the FDIC as receiver. To protect insured depositors, the FDIC created the Deposit Insurance National Bank (DINB) of Santa Clara, an institution operated by the FDIC on a temporary basis to provide insured depositors with continued access to their funds until they could open accounts at other insured institutions. The FDIC also announced its intent to provide uninsured depositors with an advance dividend against their claims for the uninsured amounts of their deposits as soon as Monday, March 13, when the DINB of Santa Clara was scheduled to reopen.18

By using a DINB and announcing an advance dividend, the FDIC hoped to minimize disruption for insured depositors and to provide a measure of immediate relief for the uninsured depositors while the agency worked to resolve the institution. The FDIC did not foreclose the possibility that another institution could purchase the deposits or assets of the failed bank, an unlikely but far preferable outcome to liquidation. Over the weekend, the FDIC actively solicited interest for a purchase and assumption of the failed bank.

Although several institutions expressed an interest in acquiring SVB, given the limited timeframe for bidders to consider making an offer, the FDIC received bids from only two institutions, only one of which provided a valid offer on the insured deposits and some of the assets of SVB.19 The costs associated with the sole valid offer would have resulted in recoveries significantly below the estimated recoveries in liquidation. Once the systemic risk determination was made, the FDIC was able to move all depositors and assets into a bridge bank and continue the operations of SVB, enabling the FDIC to engage a wider range of potential acquirers. As a result, the decision was made to conduct an expanded marketing effort of the institution on a whole-bank basis, which was anticipated to engender more and better offers.

Signature Bank Closing

Unlike SVB, which catered almost exclusively to venture capital firms, and Silvergate Bank, which was almost exclusively known for providing services to digital asset firms, Signature Bank was a commercial bank with several business lines. For example, of its approximately $74 billion in total loans as of year-end 2022, approximately $33 billion were in its commercial real estate portfolio, approximately $19.5 billion of which consisted of multifamily real estate. Signature Bank also had a $34 billion commercial and industrial loan portfolio; $28 billion of these were loans made through the Fund Banking Division, which provided loans to private equity firms and their general partners. Unlike SVB, which showed depreciation in its total securities portfolio of 104 percent to total capital, Signature Bank’s level of depreciation was approximately 30 percent.

Signature Bank’s operating model did share some of the same risk characteristics of both Silvergate Bank and SVB. Like SVB, Signature Bank grew rapidly, from $43 billion in total assets at year-end 2017 to $110 billion at year-end 2022. Growth was particularly significant from 2019 to 2020, when assets grew 64 percent. Also like SVB, Signature Bank was heavily reliant on uninsured deposits for funding. At year-end 2022, SVB reported uninsured deposits at 88 percent of total deposits versus 90 percent for Signature Bank. Signature Bank also operated a business line serving venture capital firms, although it was much smaller than that of SVB, at less than one percent of total loans and only two percent of total deposits. Moreover, in 2019, Signature Bank opened an office in San Francisco–the site of SVB’s home office–and later opened another in Los Angeles, although West Coast operations were small in relation to the overall bank.

Like Silvergate Bank, Signature Bank had also focused a significant portion of its business model on the digital asset industry. Signature Bank began onboarding digital asset customers in 2018, many of whom used its Signet platform, an internal distributed ledger technology solution that allowed customers of Signature Bank to conduct transactions with each other on a 24 hours a day/7 days a week basis. As of year-end 2022, deposits related to digital asset companies totaled about 20 percent of total deposits, but the bank had no loans to digital asset firms. Silvergate Bank operated a similar platform that was also used by digital asset firms.20 These were the only two known platforms of this type within U.S. insured institutions.

Signature Bank’s balance sheet shrank during 2022, from $118 billion in total assets and $110 billion in total deposits at year-end 2021 to $110 billion in total assets and $89 billion in total deposits at year-end 2022. In the second and third quarters of 2022, Signature Bank, like Silvergate, experienced deposit withdrawals and a drop in its stock price as a consequence of disruptions in the digital asset market due to failures of several high profile digital asset companies.21 Signature Bank met these deposit withdrawals with cash.

Signature Bank was subject to media scrutiny following the bankruptcy of FTX and Alameda Trading in November 2022, as the bank had deposit relationships with both.22 Subsequently, in December 2022, Signature Bank announced that it would reduce its exposure to digital asset related deposits.23 These declines were funded primarily by cash and borrowings collateralized with securities.

In February 2023, Signature Bank was again subject to media attention when a lawsuit was filed alleging it facilitated FTX commingling of accounts.24 Following the March 1, 2023 announcement by Silvergate Bank regarding the delay in filing its year-end 2022 financial statements and comments about its ability to continue as a going concern, Signature Bank once again experienced negative media attention, which raised questions about its liquidity position.25 This attention continued as Silvergate Bank later announced its self-liquidation.

Subsequently, as word of SVB’s problems began to spread, Signature Bank began to experience contagion effects with deposit outflows that began on March 9 and became acute on Friday, March 10, with the announcement of SVB’s failure. On March 10, Signature Bank lost 20 percent of its total deposits in a matter of hours, depleting its cash position and leaving it with a negative balance with the Federal Reserve as of close of business. Bank management could not provide accurate data regarding the amount of the deficit, and resolution of the negative balance required a prolonged joint effort among Signature Bank, regulators, and the Federal Home Loan Bank of New York to pledge collateral and obtain the necessary funding from the Federal Reserve’s Discount Window to cover the negative outflows. This was accomplished with minutes to spare before the Federal Reserve’s wire room closed.

Over the weekend, liquidity risk at the bank rose to a critical level as withdrawal requests mounted, along with uncertainties about meeting those requests, and potentially others in light of the high level of uninsured deposits, raised doubts about the bank’s continued viability.

Ultimately, on Sunday, March 12, the NYSDFS closed Signature Bank and appointed the FDIC as receiver within 48 hours of SVB’s failure.26

Systemic Risk Determination

With the rapid collapse of SVB and Signature Bank in the space of 48 hours, concerns arose that risk could spread to other institutions and that the financial system as a whole could be placed at risk. Shortly after SVB was closed on Friday, March 10, a number of institutions with large amounts of uninsured deposits reported that depositors had begun to withdraw their funds. Some of these banks drew against borrowing lines collateralized by loans and securities to meet demands and bolster liquidity positions. As previously noted, the industry’s unrealized losses on securities were $620 billion as of December 31, 2022, and fire sales driven by deposit outflows could have further depressed prices and impaired equity.

With the failure of SVB and the impending failure of Signature Bank, concerns had also begun to emerge that a least-cost resolution of the banks, absent more immediate assistance for uninsured depositors, could have negative knock-on consequences for depositors and the financial system more broadly. With uninsured depositors at the two banks likely to face an undetermined amount of losses, depositors at other banks began to move some or all of their deposits to other banks to diversify their exposures and increase their deposit insurance coverage.27 There were also concerns that investors could begin to doubt the financial strength of similarly situated institutions making it difficult and more expensive for these banks to obtain needed capital and wholesale funding.

A significant number of the uninsured depositors at SVB and Signature Bank were small and medium-sized businesses. As a result, there were concerns that losses to these depositors would put them at risk of not being able to make payroll and pay suppliers. Moreover, with the liquidity of banking organizations further reduced and their funding costs increased, banking organizations could become even less willing to lend to businesses and households. These effects would contribute to weaker economic performance, further damage financial markets, and have other material negative effects.

Faced with these risks, the FDIC Board voted unanimously on March 12, to recommend that the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the President, make a systemic risk determination under the FDI Act with regard to the resolution of SVB and Signature Bank.28 That same day, the Federal Reserve Board unanimously made a similar recommendation, and the Secretary of the Treasury determined that complying with the least-cost provisions in Section 13(c)(4) of the FDI Act would have serious adverse effects on economic conditions or financial stability, and any action or assistance taken under the systemic risk exception would avoid or mitigate such adverse effects.

The systemic risk determination enabled the FDIC to extend deposit insurance protection to all of the depositors of SVB and Signature Bank, including uninsured depositors, in winding down the two failed banks. At SVB, the depositors protected by the guarantee of uninsured depositors included not only small and mid-size business customers but also customers with very large account balances. The ten largest deposit accounts at SVB held $ 13.3 billion, in the aggregate.

The systemic risk determination does not protect any shareholders or unsecured debt holders of the two failed banks.29 The board and the most senior executives of the banks were removed. The FDIC has authority to investigate and hold accountable the directors, officers and other professional service providers of the bank for the losses they caused to the bank and for their misconduct in the management of the bank.30 The FDIC has already commenced these investigations. In accordance with the law, any losses to the DIF as the result of extending coverage to the uninsured depositors are to be recovered by a special assessment on the banking industry.31

Establishment of the Bridge Banks

After the systemic risk determination was approved on March 12, the FDIC chartered Silicon Valley Bridge Bank, N.A., (SV Bridge Bank) and transferred all deposits, both insured and uninsured, and substantially all the assets of SVB to SV Bridge Bank.32 The FDIC also chartered Signature Bridge Bank, N.A., (Signature Bridge Bank) and transferred all deposits and substantially all assets of the failed Signature Bank to Signature Bridge Bank.33

A bridge bank is a chartered national bank that operates on a temporary basis under management appointed by the FDIC.34 It assumes the deposits and certain other liabilities and purchases certain assets of a failed bank. The bridge bank structure is designed to “bridge” the gap between the failure of a bank and the time when the FDIC can stabilize the institution and implement an orderly resolution. It also provides prospective purchasers with the time necessary to assess the bank’s condition in order to submit their offers.

Depositors and borrowers of SVB and Signature Bank automatically became customers of the new bridge institutions, which reopened on Monday, March 13, with normal business activities.

Marketing and Sale of the Bridge Banks

The FDIC’s ultimate goal in operating a bridge institution is always to return the institution to private control as quickly as possible. In the context of SVB and Signature Bank, this goal was especially important, given the need to provide stability and certainty to affected depositors and customers of the banks, as well as to maintain stability and confidence in the banking system and stem the risk of contagion to other financial institutions. The FDIC opened bidding for the bridge banks on Wednesday, March 15.

Signature Bridge Bank Purchase and Assumption Agreement

Bidding for Signature Bridge Bank closed on Saturday, March 18. The FDIC received five bids from four bidders. The FDIC Board approved Flagstar Bank, N.A., Hicksville, New York, a wholly-owned subsidiary of New York Community Bancorp, Inc., Westbury, New York, as the successful bidder.

On March 19, the FDIC entered into a purchase and assumption agreement for the acquisition of substantially all deposits and certain loan portfolios of Signature Bridge Bank by Flagstar Bank, N.A. The 40 former branches of Signature Bank began operating under Flagstar Bank, N.A., on Monday, March 20. Depositors of Signature Bridge Bank, other than depositors related to the digital asset banking business, automatically became depositors of the acquiring institution. The acquiring institution did not bid on the deposits of those digital asset banking customers. The FDIC is providing those deposits, approximating $4 billion, directly to those customers.

As of December 31, 2022, the former Signature Bank had total deposits of $88.6 billion and total assets of $110.4 billion. The transaction with Flagstar Bank, N.A., included the purchase of about $38.4 billion of Signature Bridge Bank’s assets, including loans of $12.9 billion purchased at a discount of $2.7 billion. Approximately $60 billion in loans will remain in the receivership for later disposition by the FDIC. In addition, the FDIC received equity appreciation rights in New York Community Bancorp, Inc., common stock with a potential value of up to $300 million.

SV Bridge Bank Purchase and Assumption Agreement

On March 20, the FDIC announced it would extend the bidding process for SV Bridge Bank.35 While there was substantial interest from multiple parties, the FDIC determined it needed additional time to explore all options in order to maximize value and achieve the optimal outcome. The FDIC also announced it would allow parties to submit separate bids for SV Bridge Bank and its subsidiary Silicon Valley Private Bank. Qualified, insured banks and qualified, insured banks in alliance with nonbank partners would be able to submit whole-bank bids or bids on the deposits or assets of the institutions. Bank and non-bank financial firms were permitted to bid on the asset portfolios.

Bidding for Silicon Valley Private Bank and SV Bridge Bank closed on March 24. The FDIC received 27 bids from 18 bidders, including bids under the whole-bank, private bank, and asset portfolio options. On March 26, the FDIC approved First-Citizens Bank & Trust Company (First-Citizens), Raleigh, North Carolina, as the successful bidder to assume all deposits and loans of SV Bridge Bank. First-Citizens also acquired the bank’s private wealth management business. The 17 former branches of SV Bridge Bank in California and Massachusetts reopened as First-Citizens on March 27.

As of March 10, 2023, SV Bridge Bank had approximately $167 billion in total assets and about $119 billion in total deposits. The transaction with First-Citizens included the purchase of about $72 billion of SV Bridge Bank’s assets at a discount of $16.5 billion. Approximately $90 billion in securities and other assets remained in the receivership for disposition by the FDIC. In addition, the FDIC received equity appreciation rights in First Citizens BancShares, Inc., Raleigh, North Carolina, common stock with a potential value of up to $500 million.

The FDIC and First-Citizens entered into a loss-share transaction on the commercial loans it purchased of the former SV Bridge Bank.36 The FDIC as receiver and First-Citizens will share in the losses and potential recoveries on the loans covered by the loss-share agreement. The loss-share transaction is projected to maximize recoveries on the assets by keeping them in the private sector. The transaction is also expected to minimize disruptions for loan customers.

Impact on the Deposit Insurance Fund

The FDIC estimates that the cost to the DIF of resolving SVB to be $20 billion. The FDIC estimates the cost of resolving Signature Bank to be $2.5 billion. Of the estimated loss amounts, approximately 88 percent, or $18 billion, is attributable to the cost of covering uninsured deposits at SVB while approximately two-thirds, or $1.6 billion, is attributable to the cost of covering uninsured deposits at Signature Bank. I would emphasize that these estimates are subject to significant uncertainty and are likely to change, depending on the ultimate value realized from each receivership.

Under the FDI Act, the loss to the DIF arising from the use of a systemic risk exception must be recovered from one or more special assessments on insured depository institutions, depository institution holding companies, or both, as the FDIC determines to be appropriate.37 The FDI Act provides the agency with discretion in the design and timeframe for any special assessment to cover the losses from the systemic risk exception. Specifically, the law requires the FDIC to consider: the types of entities that benefit from the action taken, economic conditions, the effects on the industry, and such other factors as the FDIC deems appropriate and relevant.38 Finally, the FDI Act requires that a special assessment be prescribed through regulation.39 The FDIC intends to seek input on any special assessment from all stakeholders through notice-and-comment rulemaking and expects to issue a notice of proposed rulemaking for a special assessment related to the failures of SVB and Signature Bank in May 2023.

Current State of the U.S. Financial System

The state of the U.S. financial system remains sound despite recent events.

The FDIC has been closely monitoring liquidity, including deposit trends, across the banking industry. Since the action taken by the government to support the banking system, there has been a moderation of deposit outflows at the banks that were experiencing large outflows the week of March 6. In general, banks have been prudently working preemptively to increase liquidity and build liquidity buffers.

Over the past two weeks, banks have relied on new Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) advances to strengthen liquidity and have also pre-positioned additional collateral at the FHLB to support future draws, if needed. Banks have also prepared to access the Federal Reserve’s Discount Window and new Bank Term Funding Program by ensuring that they have pre-positioned collateral. It is important that we, as regulators, message to our supervised institutions that these facilities can and should be used to support liquidity needs. Sales of investment securities have been a less common source of liquidity as the level of unrealized loss across both available-for-sale and held-to-maturity portfolio remains elevated.

With reference to deposits, as expected, banks report that they are closely monitoring deposit trends and researching unexpected account activity. Banks report instances of corporate depositors, in particular, moving some or all of their deposits to diversify their exposures and increase their deposit insurance coverage. Banks have also reported clients moving their deposits out of the banking system and into government money market funds or U.S. Treasuries. In general, the largest banks appear to be net beneficiaries of deposit flows, increasing the amounts on deposit, or held in custody, at the global systemically important banks and at large regional banks. While some banks are reporting a moderate decline in total deposits over the past two weeks, the vast majority are reporting no material outflows.

The FDIC is also following other trends in bank activities, in particular, the steps institutions are taking to support capital and liquidity in times of market instability and uncertain deposit outlook.

More broadly, the financial system continues to face significant downside risks from the effects of inflation, rising market interest rates, and continuing geopolitical uncertainties. Credit quality and profitability may weaken due to these risks, potentially resulting in tighter loan underwriting, slower loan growth, higher provision expenses, and liquidity constraints. Additional short-term interest rate increases, combined with longer asset maturities may continue to increase unrealized losses on securities and affect bank balance sheets in coming quarters.

Preliminary Lessons Learned

In the immediate aftermath of the failure of SVB and Signature Bank, some preliminary lessons can be identified. A common thread between the failure of SVB and the failure of Signature Bank was the banks’ heavy reliance on uninsured deposits. As of December 31, 2022, Signature Bank reported that approximately 90 percent of its deposits were uninsured, and SVB reported that 88 percent of its deposits were uninsured. The significant proportion of uninsured deposit balances exacerbated deposit run vulnerabilities and made both banks susceptible to contagion effects from the quickly evolving financial developments. One clear takeaway from recent events is that heavy reliance on uninsured deposits creates liquidity risks that are extremely difficult to manage, particularly in today’s environment where money can flow out of institutions with incredible speed in response to news amplified through social media channels.

A common thread between the collapse of Silvergate Bank and the failure of SVB was the accumulation of losses in the banks’ securities portfolios. In the wake of the pandemic, as interest rates remained at near-zero, many institutions responded by “reaching for yield” through investments in longer-term assets, while others reduced on-balance sheet liquidity – cash, federal funds–to increase overall yields on earning assets and maintain net interest margins. These decisions led to a second common theme at these institutions - heightened exposure to interest-rate risk, which lay dormant as unrealized losses for many banks as rates quickly rose over the last year. When Silvergate Bank and SVB experienced rapidly accelerating liquidity demands, they sold securities at a loss. The now realized losses created both liquidity and capital risk for those firms, resulting in a self-liquidation and failure.

Finally, the failures of SVB and Signature Bank also demonstrate the implications that banks with assets of $100 billion or more can have for financial stability. The prudential regulation of these institutions merits additional attention, particularly with respect to capital, liquidity, and interest rate risk. This would include the capital treatment associated with unrealized losses in banks’ securities portfolios. Given the financial stability risks caused by the two failed banks, the methods for planning and carrying out a resolution of banks with assets of $100 billion or more also merit special attention, including consideration of a long-term debt requirement to facilitate orderly resolutions.

Conclusion

Recent efforts to stabilize the banking system and stem potential contagion from the failures of SVB and Signature Bank have ensured that depositors will continue to have access to their savings, that small businesses and other employers can continue to make payrolls, and that other banks – small, medium, and large - can continue to extend credit to borrowers and serve as a source of support. The FDIC continues to monitor developments and is prepared to use all of its authorities as needed.

The circumstances surrounding the failures of SVB and Signature Bank merit further thorough review by both regulators and policymakers. The FDIC’s Chief Risk Officer will undertake a review of the FDIC’s supervision of Signature Bank and intends to release a report by May 1, 2023. The FDIC will also undertake a comprehensive review of the deposit insurance system and will release by May 1, 2023, a report that will include policy options for consideration related to deposit insurance coverage levels, excess deposit insurance, and the implications for risk based pricing and deposit insurance fund adequacy.

The FDIC is committed to working cooperatively with our counterparts at the other federal regulators as well as with policymakers in the Congress to better understand what brought these institutions to failure and what measures can be taken to prevent similar failures in the future.

| 1 | See Silvergate Capital Corporation Press Release, Silvergate Capital Corporation Announces Intent to Wind Down Operations and Voluntarily Liquidate Silvergate Bank (March 8, 2023), available at https://silvergate.com/uncategorized/silvergate-capital-corporation-announces-intent-to-wind-down-operations-and-voluntarily-liquidate-silvergate-bank/. |

| 2 | 12 U.S.C. § 1823 (c)(4)(G). |

| 3 | See FDIC Press Release, Joint Statement by the Department of the Treasury, Federal Reserve, and FDIC (March 12, 2023), available at https://www.fdic.gov/news/press-releases/2023/pr23017.html. |

| 4 | 12 U.S.C. §1821(d)(13)(E) and (k). See also 12 U.S.C. §1818(e) and (i). |

| 5 | 12 U.S.C. §1823(c)(4)(G)(ii)(III). |

| 6 | The acquiring institutions entered into purchase and assumption agreements for the bridge banks’ deposits and assets, as described in detail later in this statement. |

| 7 | See Remarks by FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg on the Fourth Quarter 2022 Quarterly Banking Profile (February 28, 2023) available at https://www.fdic.gov/news/speeches/2023/spfeb2823.html . |

| 8 | See Silvergate Provides Statement on FTX Exposure , Businesswire (November 11, 2022), available at https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20221111005557/en/Silvergate-Provides-Statement-on-FTX-Exposure. |

| 9 | See Silvergate Capital Corporation, 4Q22 Earnings Presentation (January 17, 2023), available at https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1312109/000131210923000020/ex992si4q22earningsprese.htm. |

| 10 | Ibid. |

| 11 | See Silvergate Capital Corporation Form 12b-25, Notification of Late Filing, available at https://silvergate.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/notification312023.pdf. |

| 12 | See Silvergate Capital Corporation Press Release, Silvergate Capital Corporation Announces Intent to Wind Down Operations and Voluntarily Liquidate Silvergate Bank (March 8, 2023), available at https://silvergate.com/uncategorized/silvergate-capital-corporation-announces-intent-to-wind-down-operations-and-voluntarily-liquidate-silvergate-bank/. |

| 13 | See Silicon Valley Bank’s FFIEC Call Report filings from December 31, 2019, and December 31, 2022. |

| 14 | See Silicon Valley Bank Strategic Actions/Q1 2023 Mid-Quarter Update (March 8, 2023), available at https://s201.q4cdn.com/589201576/files/doc_downloads/2023/03/Q1-2023-Mid-Quarter-Update-vFINAL3-030823.pdf. |

| 15 | See SVB Financial Group Form 8-K (March 8, 2023), available at https://www.sec.gov/ix?doc=/Archives/edgar/data/719739/000119312523064680/d430920d8k.htm. |

| 16 | See New York Times , “Silicon Valley Bank’s Financial Stability Worries Investors” (March 9, 2023), available at https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/09/business/silicon-valley-bank-investors-worry.html. |

| 17 | Ibid. |

| 18 | See FDIC Press Release, FDIC Creates a Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara to Protect Insured Depositors of Silicon Valley Bank, Santa Clara, California (March 10, 2023), available at https://www.fdic.gov/news/press-releases/2023/pr23016.html. |

| 19 | The other institution failed to submit a resolution from its board of directors authorizing its offers on SVB; therefore, the offers could not be considered. |

| 20 | See CoinDesk, Silvergate Closes SEN Platform Institutions Used to Send Money to Crypto Exchanges (March 3, 2023), available at https://www.coindesk.com/policy/2023/03/03/silvergate-suspends-sen-exchange-network. |

| 21 | See Bloomberg, A $60 Billion Crypto Collapse Leads to a New Type of Bank Run (May 19, 2022), available at at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-05-19/luna-terra-collapse-reveal-crypto-price-volatility?leadSource=uverify%20wall. |

| 22 | See Businesswire, Signature Bank Provides Digital Asset Banking Update (November 15, 2022), available at https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20221115006076/en/. See also Seeking Alpha, Silvergate gives mid-quarter update after FTX collapse; stock slips (November 16, 2022), available at https://seekingalpha.com/news/3908970-silvergate-gives-mid-quarter-update-after-ftx-collapse-stock-slips. |

| 23 | See PYMNTS, Signature Bank Tries to Distance Itself from Crypto (December 6, 2022), available at https://www.pymnts.com/cryptocurrency/2022/signature-bank-tries-to-distance-itself-from-crypto/. |

| 24 | See CoinDesk, Signature Bank Sued for ‘Substantially Facilitating’ FTX Comingling (February 7, 2023), available at https://www.coindesk.com/business/2023/02/07/signature-bank-sued-for-substantially-facilitating-ftx-comingling/. |

| 25 | See Crain’s New York Business, Signature Bank warns its growth could be impacted if the cryptocurrency world suffers another downdraft (March 6, 2023), available at https://www.crainsnewyork.com/finance/signature-bank-warns-its-growth-could-be-impacted-if-cryptocurrency-world-suffers-another. |

| 26 | See FDIC Press Release, FDIC Establishes Signature Bridge Bank, N.A., as Successor to Signature Bank, New York, NY (March 12, 2023), available at https://www.fdic.gov/resources/resolutions/bank-failures/failed-bank-list/signature-ny.html. |

| 27 | Depositors also moved funds to Treasury securities and government money market funds. |

| 28 | 12 U.S.C. § 1823(c)(4)(G). |

| 29 | The FDIC as receiver for a failed bank routinely affirms the bank’s obligations to providers of services, such as, for example, IT contractors and utility companies, because the payment of these obligations is necessary for the administration of the bank’s receivership. 12 U.S.C. § 1821(d)(2)(B) & (d)(11). |

| 30 | The FDIC as receiver for SVB and Signature Bank will pursue all civil actions against directors, officers, and professional service providers of the former banks that are meritorious and cost-effective, as permitted under state federal law. Additionally, the FDIC in its supervisory capacity may pursue administrative enforcement actions against SVB’s officers and directors and institution-affiliated parties, including the assessment of civil money penalties and prohibitions from the banking industry, where the individual’s misconduct evidences personal dishonesty, recklessness, or a willful or continuing disregard for the safety and soundness of the institution. 12 U.S.C. §1818(e) & (i). |

| 31 | 12 U.S.C. §1823(c)(4)(G)(ii). |

| 32 | See FDIC Press Release, FDIC Acts to Protect All Depositors of the former Silicon Valley Bank, Santa Clara, California (March 13, 2023), available at https://www.fdic.gov/news/press-releases/2023/pr23019.html. |

| 33 | See FDIC Press Release, FDIC Establishes Signature Bridge Bank, N.A., as Successor to Signature Bank, New York, NY (March 12, 2023), available at https://www.fdic.gov/news/press-releases/2023/pr23018.html. |

| 34 | 12 U.S.C. §1821(n). |

| 35 | See FDIC Press Release, FDIC Extends Bid Window for Silicon Valley Bridge Bank, N.A. (March 20, 2023), available at https://www.fdic.gov/news/press-releases/2023/pr23022.html. |

| 36 | For more information on FDIC loss share transactions, see https://www.fdic.gov/resources/resolutions/bank-failures/failed-bank-list/lossshare/index.html |

| 37 | 12 U.S.C. §1823(c)(4)(G)(ii)(I). |

| 38 | 12 U.S.C. §1823(c)(4)(G)(ii)(III). |

| 39 | Ibid. |